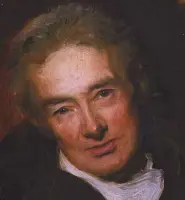

WILLIAM WILBERFORCE

|

William Wilberforce (1759-1833), abolitionist and philanthropist, was born to a family of merchants.He was first educated at Hull Grammar School under Joseph Milner, an evangelical Anglican minister. His father died when Wilberforce was nine, and his mother sent him to stay near London where he was reared by an evangelical aunt and uncle. Through their influence, he came to faith at the age of 12. In this home he came into contact with such men as George Whitefield, the great evangelist, and John Newton, who had converted from a life of a slave trade, and ultimately penned the hymn Amazing Grace. |

Wilberforce's mother and other close family friends were alarmed at young William's religious "enthusiasm" and sought to reverse this course.By the time he arrived at St. John's College at Cambridge in 1776, his evangelicalism was well behind him, and he was as worldly as any of his friends, and vastly popular. Witty, charming, erudite, eloquent and hospitable, not to mention exceedingly wealthy, Wilberforce as an undergraduate displayed the charisma of a natural leader who drew friends and followers into his world. |

In 1779, Wilberforce moved to London where he became friends with William Pitt.Both were motivated to enter politics and Wilberforce was elected to Parliament in September 1780 at the age of 21, the youngest age at which one could be elected. Pitt was soon to be Chancellor of the Exchequer and by the age of twenty-four Britain's Prime Minister, and because Wilberforce and Pitt were inseparable, the political career of this son of a tradesman advanced quickly. In 1784, while respected as one of Parliament's leading debaters, Wilberforce decided on a European tour and invited an Irish friend to accompany him. When the friend declined, Wilberforce asked Isaac Milner, the brother of Joseph Milner (his former schoolmaster) to join him. Isaac, an Anglican clergyman, was known as a brilliant Cambridge scientist and mathematician. |

|

Unaware of Milner's evangelical convictions, Wilberforce was surprised to find that someone whom he could respect intellectually could also embrace a Christian worldview. Together they read and reviewed the Greek New Testament and Philip Doddridge's The Rise and Progress of Religion in the Soul. By the end of two European trips, the politician was convicted of his sin. He acknowledged:

A sense of my great sinfulness in having so long neglected the unspeakable mercies of my God and Savior. |

At this time, Wilberforce sought counsel from John Newton, by then the leading Anglican evangelical in London, and by October 1785 the 'great change' became complete.

For a time Wilberforce thought about a call to ministry and retiring from public life, but Newton and Pitt urged him to stay in Parliament and serve Christ there. Pitt said, “Surely the principles as well as the practice of Christianity are simple, and lead not to meditation only but to action” (The Private Papers of William Wilberforce, 1897, p. 13).

After a long period of self-questioning and prayer, Wilberforce reached his famous conclusion.

"God had set before me two objects: the suppression of the slave trade and the reformation of manners"

While due in part to the influence of Newton, a former slave trader, Wilberforce's embracing of the anti-slavery cause was from the direct effect of embracing the Christian worldview. But this was not a popular cause. Wilberforce was the target of tirades and assassination threats. Admiral Nelson wrote that as long as he would speak and fight he would resist "the damnable doctrines of Wilberforce and his hypocritical allies." An irate sea-captain pummeled Wilberforce on the street. It was whispered slanderously when he was yet unmarried that his wife was black and that he beat her. His friends were accused of being spies in the service of the French. Despite threats to his life, he put forward a bill in the House of Commons in 1793 advocating gradual abolition. It failed by eight votes, most members absenting themselves from the House so as not to have to vote. Next, he brought forward a bill prohibiting British ships from carrying slaves to foreign territories. It lost by two votes in a near-empty House. Promised the support of some Members of Parliament, he found himself abandoned. Although Wilberforce reintroduced the Abolition Bill almost every year in the 1790s, little progress was made even though Wilberforce remained optimistic for the long-term success of the cause.

|

In the meantime, Wilberforce directed some of his efforts into other arenas, largely evangelical or philanthropic.One historian has calculated that Wilberforce was a member of the committee of some sixty-nine voluntary societies. In addition to his abolition work, he was consistently involved in church work that included the Church Missionary Society and the sending of missionaries to India and Africa, the British and Foreign Bible Society, the Proclamation Society Against Vice and Immorality, the School Society, the Sunday School Society, the Society for Bettering the Condition of the Poor, the Vice Society and others. |

His public philanthropic efforts were many, including relieving the suffering of the manufacturing poor, and French refugees and foreigners in distress. History records Wilberforce as having made major financial contributions to at least seventy such societies, and as being active in numerous reform movements which included reform in hospital care, fever institutions, asylums, infirmaries, refugees and penitentiaries. He supported religious publications and education, especially the schools of Hannah More, a close friend and leading reformer of British education (Gathro, William Wilberforce and His Circle of Friends).

In 1797 he published a book, A Practical View of the Prevailing Religious System of Professed Christians.A work of popular evangelical theology that was highly influential and sold well on publication and throughout the nineteenth century. It was also that year, at the age of 37, after a short romance, he married Barbara Ann Spooner, beginning 'thirty-five years of undiluted happiness'. Over the next 10 years, his family life became even busier with the birth of four sons and two daughters. Wilberforce viewed his own role as father as more important than his role as politician. Wilberforce's resolve to end slavery never abated. |

He was joined in his efforts by like-minded Christian friends known as the “Clapham Sect”.For twenty years they labored to turn public opinion and political leaders against the evils of slavery and the tide began to turn. On the night of February 23, 1807, excitement grew in the House of Commons as his latest motion was debated. Speech after speech spoke in favor of abolition, and his fellow members began to pay tribute to Wilberforce. The climax came when Solicitor General Sir Samuel Romilly contrasted the reception that Napoleon and Wilberforce would receive at the end of a day’s labors: Napoleon would come home in power and pomp, yet tormented by the bloodshed and oppression of war he had caused. |

|

“Wilberforce would come home to ‘the bosom of his happy and delighted family,’ able to lie down in peace because he had ‘preserved so many millions of his fellow creatures."

The House of Commons rose to its feet, turned to Wilberforce, and began to cheer. They gave three rousing hurrahs while Wilberforce sat with his head bowed and wept.” (Belmonte, Hero for Humanity, p. 148) Then the Commons voted to abolish the slave trade by a vote of 283 to 16. Prime Minister Granville called the passage. |

The House of Commons rose to its feet, turned to Wilberforce, and began to cheer.

They gave three rousing hurrahs while Wilberforce sat with his head bowed and wept.” (Belmonte, Hero for Humanity, p. 148) Then the Commons voted to abolish the slave trade by a vote of 283 to 16. Prime Minister Granville called the passage.

A measure which will diffuse happiness among millions now in existence, and for which his memory will be blessed by millions yet unborn.

Wilberforce went on to lobby the governments of other nations, including the US, to adopt similar measures, and to assure that the laws were enforced.

After stopping the trading of slaves, he devoted himself for the next 25 years to ending the institution of slavery itself. Three days before his death in 1833, he heard that the House of Commons had passed a law emancipating all slaves in the British Empire.

Wilberforce’s faith in Jesus Christ changed him from a careless, wealthy young politician to a tireless, compassionate public servant. He developed and used his gifts of leadership and persuasion to champion countless efforts to better society. He was a moral leader who voted against his party when principle required it. His partnership with his Christian brothers and sisters in the Clapham Sect serves as a model for Christians working together to bring about meaningful reform in society. He persisted for decades in the tasks God had called him to, despite illness, physical threats, and enormous opposition. At his death the British nation honored Wilberforce by burying him in Westminster Abbey and erecting a statue in his memory. |

For all of these reasons, Wilberforce is a man we hold up for our children to learn from and emulate.

"William Wilberforce...was a great man who impacted the Western world as few others have done. Blessed with brains, charm, influence and initiative, much wealth … he put evangelicalism on Britain's map as a power for social change, first by overthrowing the slave trade almost single-handed and then by generating a stream of societies for doing good and reducing evil in public life… To forget such men is foolish."

- J.I. Packer